|

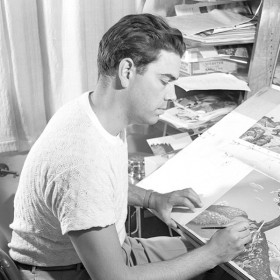

| Image courtesy of cartoonresearch.com |

On this day, in 1913, John Frederick Hannah was born in Nogales, Arizona. Another Legend that it's hard to find background information on (other than he enjoyed hunting with his dad), we pick Jack's story up in 1931. He'd made his way to Los Angeles and was attending the Art Guild Academy. As a student, one of the first jobs he managed to get was designing movie posters for local theaters. As the Great Depression ground on, Jack made a visit to the Walt Disney Studio to try for a job. His portfolio was deemed good enough and, in 1933, he began his animation career as an inbetweener on Mickey Mouse shorts.

Jack had moved up to full animator by 1937, when his contributions to

The Old Mill helped win an Academy Award for the studio. After slaving over the drawing board for 12 more shorts, Jack moved over to the story department and started writing for Donald Duck shorts. From 1939-43, he wrote 27 stories for the cantankerous fowl, sometimes collaborating with the legendary Carl Barks, including

Donald Gets Drafted (where we learned Donald's middle name is Fauntleroy). Jack and Carl would also work together on the first couple of Donald comic books. Carl would leave the studio for the comic world full time, but Jack stuck around and became a director.

|

| Image copyright Disney |

The 1944 short

Donald's Off Day was the onset of Jack's spectacular run of feathered mayhem surrounding the perennial second banana at the Disney studio. Over the next decade, he would helm 94 shorts, most of them featuring Donald. Jack would introduce the world to classic foils for his fowl friend, including Chip and Dale and Humphrey the Bear. He was so prolific in developing Donald's character that more than one Disney historian has referred to him as "Donald Duck's Other Daddy."

As the studio began winding down short production in the mid Fifties, Jack tried to make the transition to television. He was able to direct several episodes of the

Disneyland series, all of them involving Donald, usually having conversations with Walt. He tried to get Walt to let him direct more live-action projects, but claims that Walt had him pigeon-holed as an animation guy and wouldn't do it. Whether or not that was true, Jack would retire from the Disney Studio in 1957, mildly disgruntled. He wouldn't stop working though.

|

| Image courtesy of 2917hyperion.blogger.com |

Following his departure from Disney, Jack went to work for another animation legend, Walter Lantz. For the next several years, he directed Woody Woodpecker shorts and became Assistant Director on Lantz's television project,

The Woody Woodpecker Show. In 1963, he retired a second time.

By the mid Seventies, Disney was starting to feel the pinch as all of the original crew of animators were retiring (or passing away) and a vacuum was being created with no readily available replacements. Studio executives approached Jack with a proposal to jump start the Character Animation program at Cal Arts. He teamed up with T. Hee to create it and actually taught classes himself for the next eight years. Countless members of the current pantheon of animators cut their teeth studying under Jack and the fabulous Cal Arts program.

In 1992, Jack was made an official Disney Legend, not only for all his shepherding of Donald but for basically ensuring the continuation of the medium in general. Two years later, he would pass away on June 11, 1994 in Burbank, California. He was 81.