On this day, in 1916, Hamilton Henry Gilkyson III was born in

Phoenixville, Pennsylvania. Known as Terry most of his life, he grew up in

a close knit family where, like many folks living through the Roaring Twenties

and the Great Depression, music formed the bulk of their entertainment. Terry

found it interesting enough that he became a music student at the University of

Pennsylvania. He chaffed under the structure of classwork, however, and dropped

out after two years. He then moved out to Tucson, Arizona in 1937 and began

working as a ranch hand on a friend’s big spread. In his spare time, he learned

how to play guitar and write folk songs. When World War II came to America, he

joined the United States Army, serving first in the cavalry then moving on to

the Army Air Corps. Following his discharge at the end of the war, Terry

returned to Pennsylvania, took over his father’s insurance company and got

married. But the siren song of a career in music proved too strong to resist.

In 1947, Terry and his new bride, Jane, relocated to Los Angeles,

California. In 1948, he landed his first professional music gig on Armed Forces

Radio as The Solitary Singer. The next year he recorded

The Cry of the Wild

Goose, a song he also wrote. A version sung by Frankie Laine became a hit

in 1950. Throughout the first half of the Fifties, Terry produced three albums

for Decca Records, sang two hits with a group called The Weavers (

On Top of Old Smoky

and

Across the

Wide Missouri), wrote another hit song for Frankie (

Tell Me a Story)

and began appearing in small roles in movies, frequently writing the music for

them as well. (1951’s

Slaughter Trail).

|

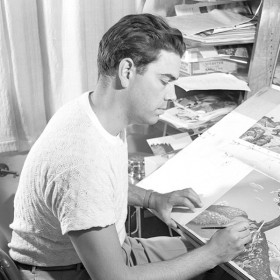

| Image courtesy allmusic.com |

In 1953, he joined a group called The Easy Riders. The trio prospered in an

era of political uncertainty (damn you, Joe McCarthy!) by studiously avoiding

controversial topics, something most folk singers of the time (or any time

really) were unable to do.

The Riders released one song, Marianne, that went gold (meaning it sold over a

million copies) in 1957 and wrote the song

Memories

Are Made of This which became a hit for Dean Martin (with backing vocals by…

The Easy Riders!). Terry continued writing songs by himself throughout the

decade, creating several folk standards that would be recorded by Burl Ives,

The New Christie Minstrels and even Harry Belafonte. One of his last

compositions with the Riders would be

Greenfields, which became a hit for The

Brothers Four.

|

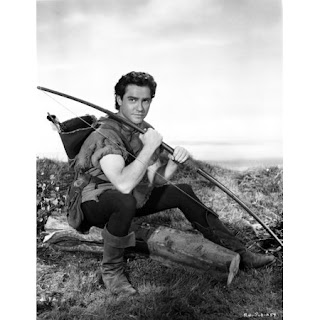

| Image copyright Disney |

In the early Sixties, Terry dropped out of The Easy Riders and started

writing songs for the Walt Disney Company. Some of his work from this period

includes

My Heart Was an Island from

Swiss Family Robinson,

Savage Sam and Me from

Savage Sam (the sequel to

Old Yeller), Thomasina from

The Three Lives of Thomasina and the

title song from

The Moon-Spinners. In

1967, Terry wrote several songs for the studio’s 19

th animated

feature,

The Jungle Book, as did the Sherman Brothers. Only one of his actually

made it into the film (Walt felt most of them were too dark), but it’s the one everybody

knows and hums along with,

The Bare

Necessities. Terry’s song was also the only part of The Jungle Book to earn

an Oscar nomination, his one and only shot at an award (he lost to

Talk to the Animals from

Dr. Doolittle). His final contribution

to the company came in 1970’s

The

Aristocats with the song

Thomas O’Malley

Cat.

Following the success of his work in

The

Jungle Book and

The Aristocats,

Disney asked Terry to sign on with the company full time, instead of the

contract work he’d been doing up to that point. He was leery of the offer,

however, afraid that he would no longer have rights to his own songs. Rather

than accept, Terry chose to retire altogether. He spent the remainder of his

life watching his three kids build careers in the music industry. While

visiting family in Austin, Texas, he passed away on October 15, 1999. He was

83.